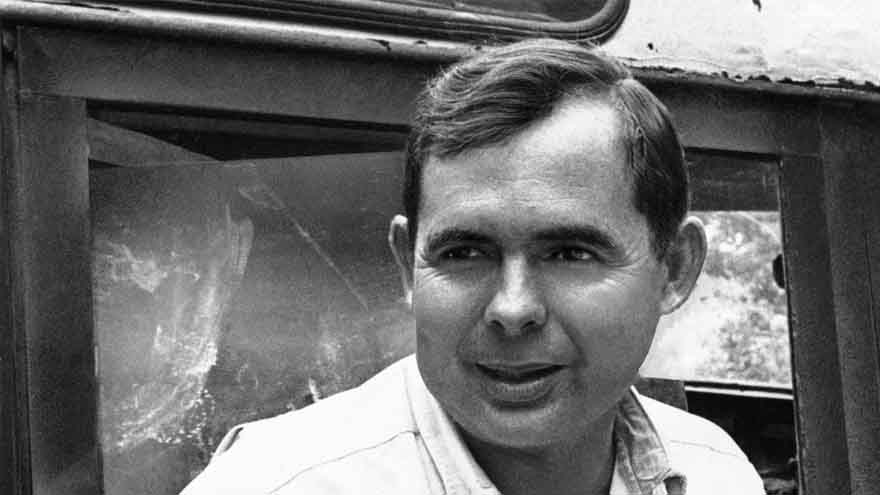

Patrick Hemingway, Ernest Hemingway's last surviving child, dies at 97

Entertainment

Hemingway, the second of the author’s three sons, died at his home in Bozeman, Montana

NEW YORK (AP) — Patrick Hemingway, the last surviving child of Ernest Hemingway who was inspired by his father to spend years in Africa and later oversaw numerous posthumous works by the Nobel laureate, died Tuesday at age 97.

Hemingway, the second of the author’s three sons, died at his home in Bozeman, Montana, his grandson, Patrick Hemingway Adams, confirmed in a statement.

“My grandfather was the real thing: a larger than life paradox from the old world; a consummate dreamer saddled with a scientific brain. He spoke half a dozen languages and solved complicated mathematical problems for fun, but his heart truly belonged to the written and visual arts,” Adams said.

While brother Gregory Hemingway had a deeply troubled relationship with his famous parent, Patrick Hemingway spoke proudly of his background and welcomed the chance to bring up the family name or get behind a project he thought could sell or attract critical attention. In the 2022 book “Dear Papa: The Letters of Patrick and Ernest Hemingway,” father and son share stories of hunting and fishing and express mutual affection, with the author telling Patrick that “I would rather fish with you and shoot with you than anybody that I have ever known since I was a boy and this is not because we are related.”

As an executor of his father’s estate, Patrick Hemingway approved reissues of such classics as “A Farewell to Arms” and “A Moveable Feast,” featuring revised texts and additional commentary from the author’s son and others. The estate also unsettled Hemingway admirers by expanding beyond books and offering a line of products that included clothing, eyewear, rugs and “Papa’s Pilar Rum.”

Patrick’s most ambitious undertaking was the editing of “True at First Light,” a fictionalized account of Ernest Hemingway’s time in Africa in the mid-1950s that the author left unfinished at the time of his death. Patrick assembled the 1999 release from some 800 pages of manuscripts, cutting the length by more than half. “True at First Light” was highly anticipated, but ended up disappointing readers and critics, some of whom faulted Patrick for exploiting the family name.

Asked by NPR if he read his father’s work, Patrick replied: “Pretty often, because I have a commercial interest. ... I have to read it in order to be competent in the marketing of it and the management of it.”